Witchcraft, Gender, and Law: A Historical Examination by Professor Alison Rowlands from the University of Essex.

Our sixteenth- and seventeenth-century ancestors believed that harming witches possessed a malevolent magical power that could make harvests fail and cause people and animals to fall ill or die. A magical attack on the health of a loved one was most feared and most likely to prompt an accuser to take legal action against a suspected witch.

This fear of the malevolent power of witchcraft is clear in many of the cases brought against alleged witches in the Tendring Hundred (see the exhibition boards on the trail for more detail). Another example of this fear can be seen in the case brought against Mary Johnson, the wife of a sailor called Nicholas Johnson of Wivenhoe, Essex, in 1645. Mary was accused by Annabel Durrant of Fingringhoe of being responsible for the death of Annabel’s two-year-old son, after they had met Mary while out walking one day. Annabel claimed that Mary had stroked the boy’s face, called him ‘a pretty child’, and given him a piece of bread-and-butter. Immediately after eating the bread, the child had fallen ill. He had died eight days later, ‘shrieking and tearing’ himself. Nowadays we would understand that the illness the child experienced could not have been caused by Mary’s touch and gift; sadly, this was one way in which people who lived in earlier centuries explained and tried to make sense of suffering and grief. The tragic aspect of this belief in harmful magic was that it was always linked to – and blamed on – a specific (usually female) individual in the local community, who was known to the accuser. A formal accusation of witchcraft thus constituted a complete breach of trust between neighbours, which might end in the execution of the accused.

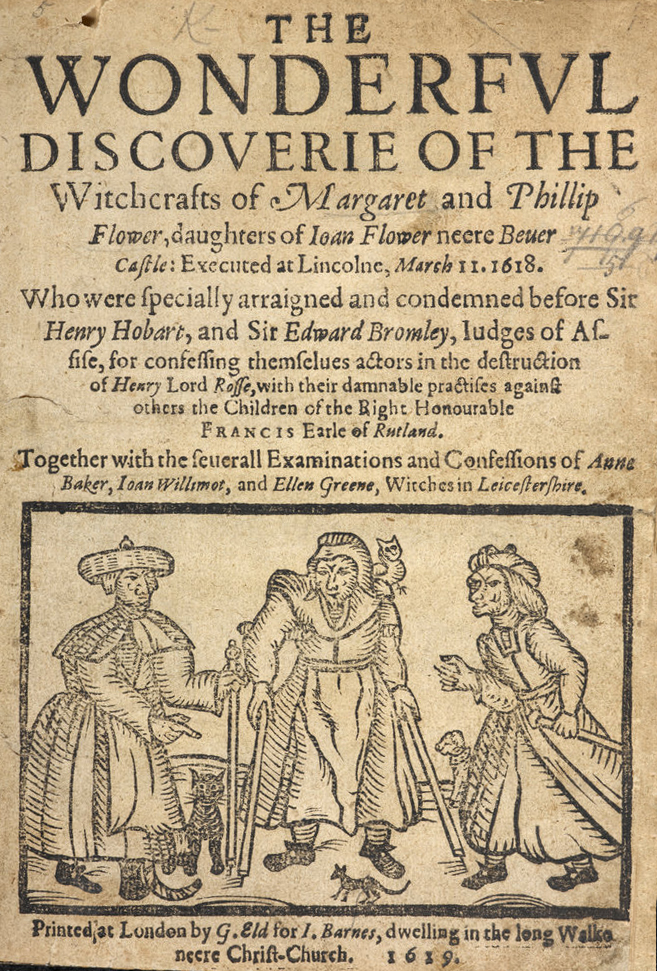

The malevolent English witch was often imagined to possess a ‘familiar’, an evil spirit that usually looked like a demonic version of a small animal such as a cat, rat, dog, mole, ferret, toad or bird. Other familiars were more fantastical, such as Vinegar Tom, the greyhound with the head of a calf that featured in the confessions of Elizabeth Clarke of Manningtree in 1645. In return for being fed and housed by the alleged witch, the familiar was thought to help the witch work her harmful magic. For example, in 1645 Elizabeth Otley of Wivenhoe said that Mary Johnson had killed her daughter by sending a rat-like familiar into the Otleys’ house to rock the child’s cradle. Belief in familiars mattered to the courts, as it was believed that an alleged witch would have a mark or teat on her body from which her familiar suckled that was insensible to pain. This idea led to some of the worst abuses of the legal process against suspected witches, as those accused in the East Anglian witch-trials of 1645-7 were subjected to degrading and painful body searches for such marks. The familiar was also evidence of the witch’s supposed allegiance with the devil. Demons in human form began to appear in English witch-trials in the seventeenth century, with Elizabeth Clarke of Manningtree the first suspect to be forced into confessing that she had had sex with the devil in human form in 1645. Witch-trials in Scotland and elsewhere in Europe were much more strongly dominated by the belief that witches made pacts with a human-like devil, but in England the witch’s supposed relationship with her familiar remained central.

People also looked to good or white magic to protect themselves against harmful witchcraft, disease, and misfortune. Practitioners of white magic were known as cunning folk in England; they drew on a combination of herbal remedies and semi-religious and magical ritual to offer their customers solutions for their problems. Occasionally a cunning woman was accused of harmful magic; this happened to Ursula Kemp of St Osyth in 1582 (see trail board for more information). However, ordinary people were usually reluctant to send their local cunning folk to court. This may have been because most of them were men; around 70% of the cunning folk identified in historical sources for sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Essex were men.

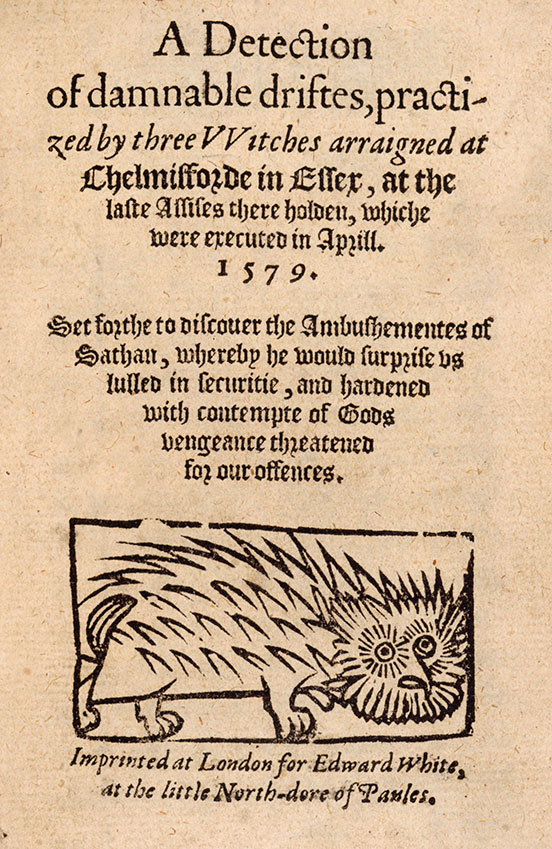

Witchcraft was criminalised in England by Acts of Parliament issued in 1542, 1563 and 1604. The 1542 English Act against conjurations and witchcraft and sorcery and enchantments was, however, seldom used and repealed in 1547. Of far more importance to the history of English witch-prosecution was the Act against conjurations, enchantments and witchcraft that was passed in 1563, at the start of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (ruled 1558-1603). This Act made murder by witchcraft a felony, punishable by death by hanging. It imposed the lesser punishment of a year in prison, with four six-hour appearances in the pillory, for anyone convicted of harming (but not killing) a person or damaging or destroying their goods or livestock by magic. A second such offence was also punishable by hanging.

The 1563 Act was replaced in 1604 with the Act against conjuration, witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked spirits. The 1604 Act was more severe than its predecessor, making even non-fatal harmful witchcraft into an immediate capital offence. The 1604 Act also made it a capital offence to ‘consult, covenant with, entertain, employ, feed or reward any evil and wicked spirit’, thereby criminalising the keeping of a familiar. The 1604 Act was passed shortly after James I (ruled 1603-1625) came to the English throne. As King of Scotland (ruled 1567-1625), James believed he had been the personal target of witches’ harmful magic in the North Berwick witch-trials of 1590-1591. He was also the only monarch to write a book about witches: Daemonologie, published in 1597.

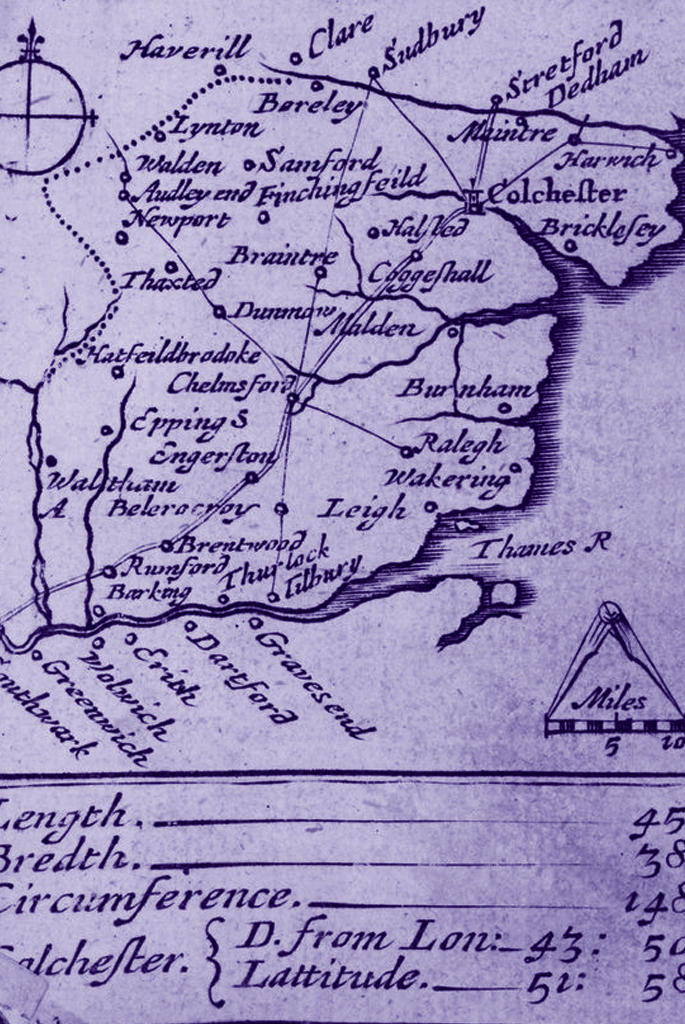

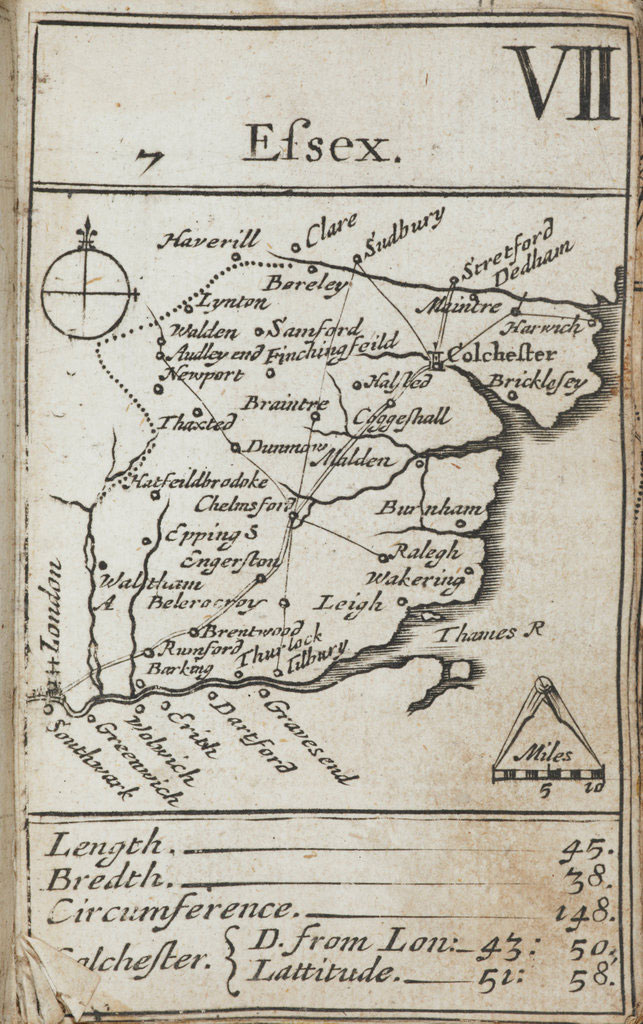

People accused by their neighbours of harmful witchcraft were tried under the 1563 and 1604 Acts before courts of criminal law. This usually meant the Assize Courts, which were held twice a year and overseen by royal judges sent out from London on Assize Circuits. Chelmsford was the main site of the Assize Court in Essex, although some alleged witches were tried in Borough Courts (for example, in Colchester, Maldon, and Harwich) which held rights of criminal jurisdiction. An accused witch would first be questioned by the Justice of the Peace local to their village or town, then taken into custody if the Justice of the Peace believed there was a charge to answer. People accused of witchcraft in the Tendring Hundred were usually held in the gaol at Colchester Castle, then sent by cart to Chelmsford for the spring or summer Assize. This meant that they might spend weeks imprisoned in poor conditions before their trials; four Tendring Hundred women died of the plague in Colchester Castle in 1645 before they could be sent to Chelmsford.

Trials were short and rules of evidence lax by our standards. Witchcraft was a hard crime to prove, so great emphasis was placed on a suspect’s reputation and behaviour, especially in relation to their verbal aggression. Physical evidence, in the form of marks or teats on the alleged witch’s body from which their familiars supposedly suckled, was also important in some cases. However, the key factor in most trials was the accuser’s willingness to believe that the misfortune they had suffered had been caused by the suspected witch and the jurymen’s willingness to convict on this basis. Even then, a high proportion of English trials resulted in acquittals or (before 1604) non-capital punishment. Trials and executions for witchcraft also stopped relatively early in England. The last executions took place in Devon in 1682, the last trials in Leicester in 1717. The 1604 Act was replaced by the Witchcraft Act of 1735, which decriminalised harmful witchcraft and said that all magical practice – including the magical services offered by cunning folk – was fraudulent. The 1735 Act showed that the governing elites of eighteenth-century England were no longer willing to take witchcraft seriously, although many ordinary people carried on believing in it (and taking unofficial action against suspected witches) until well into the nineteenth century.

This article gives an overview of the number of trials and executions for witchcraft that took place in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England and Essex. I would like to begin by saying that even one execution of someone for what we would nowadays regard as the impossible crime of harmful witchcraft is abhorrent. By our modern standards, these were all executions of innocent people. However, we need to remember that people living in earlier centuries had different beliefs, which included the idea that humans could make deals with evil spirits and kill their neighbours through magic. Once these actions were criminalised by the governing authorities (see the Witchcraft Legislation article for more detail), trials and executions were possible.

Precise numbers of the trials and executions for witchcraft that took place across Europe between the fifteenth and eighteenth century are difficult to ascertain; the original legal records do not survive completely for all regions and research into the subject is still ongoing. However, historians know enough about the worst episodes of prosecution to arrive at fairly accurate summary numbers. On this basis, we know that England had around 500 executions for witchcraft between 1564 (when the first execution occurred) and 1682 (which saw the last executions). This was out of a total of around 50,000 executions for witchcraft in the whole of Europe between the fifteenth and eighteenth century, making England’s witch-trials (in comparative terms) less severe than those of Scotland (which had as many as 1300-1500 executions from a lower total population) and Germany (which saw around 25,000 executions). In England, trials spread from the southeast (the first centre of prosecutions), to the south Midlands (in the late Elizabethan period), the Midlands and Lancashire (under James I), and then to northern and western areas (Devon, Cornwall, Yorkshire, Durham). Essex (in 1582 and 1645), Lancashire (in 1612 and 1634), and Suffolk and Norfolk (in 1645) had some of the largest trials. The East Anglian witch-trials of 1645-7, which began in Essex and then spread to Suffolk, Norfolk, Huntingdonshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire, and the Isle of Ely, constituted the largest single episode of witch-prosecution in English history. It occurred during the English Civil War and became associated with the zealous Puritanism and popular radicalism of the Civil War years, both of which fell out of favour after the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660. Thereafter enthusiasm for trials and executions declined.

Witch-trials in Essex began quickly after the passing of the 1563 Witchcraft Act, with the first execution – of Elizabeth Lowys of Great Waltham – in 1564. The last Essex person tried at the Assize Court was Elizabeth Gynn of Great Dunmow in 1675, when the charge against her of bewitching Edmund, the nine-year-old son of her neighbour Roger Treddar, to death was dismissed. Essex experienced its two most intense periods of prosecution in the late-sixteenth century and 1645. The 1580s and 1590s were a time of socio-economic crisis, during which population increase and harvest failures pushed grain prices up dramatically, thereby increasing people’s anxiety about their ability to feed their families. After a decline in trials in the early-seventeenth century, the second intense Essex prosecution occurred in 1645, in the context of the religious and political tension of the English Civil War. This year saw the East Anglian witch-trials begin in Manningtree, with 19 women from the Tendring Hundred hanged for witchcraft (see the Manningtree trail-board for more details). Overall, we know that between 1560 and 1680, 291 people were accused of witchcraft before the Essex Assize Courts, of whom 151 were found not guilty or had the charges against them dismissed. Of the remaining 140, 129 were convicted, with 74 of them hanged and 55 imprisoned for a year (as per the 1563 Witchcraft Act). At least 36 accused witches also died in gaol in Essex, either while awaiting their trials or after being convicted and imprisoned, bringing the overall death toll to at least 110. The Tendring Hundred was one of two Essex regions which suffered particularly intense witch-prosecutions. This was mainly due to the St Oysth witch-trials of 1582, the Harwich trials of the early seventeenth century, and the trials that began in Manningtree in 1645 (see trail-boards for more detail).

Overall, we know that between 1560 and 1680, 291 people were accused of witchcraft before the Essex Assize Courts, of whom 151 were found not guilty or had the charges against them dismissed. Of the remaining 140, 129 were convicted, with 75 of them hanged and 55 imprisoned for a year (as per the 1563 Witchcraft Act). At least 36 accused witches also died in gaol in Essex, either while awaiting their trials or after being convicted and imprisoned, bringing the overall death toll to at least 110. The Tendring Hundred was one of two Essex regions which suffered particularly intense witch-prosecutions. This was mainly due to the St Oysth witch-trials of 1582, the Harwich trials of the early seventeenth century, and the trials that began in Manningtree in 1645 (see trail-boards for more detail).

In England, nearly 90% of all those accused of harmful witchcraft were women, a figure higher than the European average of 75-80%. In Essex, 268 of the 291 people tried for harmful witchcraft were women (about 92%). Of the 23 men tried in Essex, eleven were married to a woman who was also accused of witchcraft or appeared on a joint charge with a woman. These figures show that, while the English Witchcraft Acts did not specify the gender of witches, most of those who ended up in court and on the gallows were women.

The gendering of witch-prosecution had several interlinked causes. The patriarchal structure of society meant that most women were relatively disadvantaged when compared with most men. Women had less legal and socio-economic power and were less likely to be literate than men, so were less able to defend themselves against accusations of witchcraft. Harming witchcraft was more readily associated with women than men, while women were portrayed as weaker in faith and more vulnerable to temptation in the religious and medical thinking of the time. This made it easier for people to imagine that women would be tempted into witchcraft by the forces of evil and that they were more likely than men to resort to magic (instead of physical violence or a more formal type of power) in social interactions. There is some evidence that women aged between 50 and 70 were particularly vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft in Essex. This was because they were more reliant on their neighbours for loans and gifts of food, and more likely to see their requests for charity refused in the sixteenth and seventeenth century as population increase put pressure on resources. An older woman who cursed her neighbours in anger if she did not receive the help she expected risked being accused of witchcraft if the neighbours subsequently suffered misfortunes that they blamed on her, to ease their consciences about their own unneighbourly behaviour.

This ‘charity-refused’ way of explaining accusations is just one part of the picture, however. We only know the ages of 15 women accused of witchcraft in Essex, so cannot assume they were all old. We also have incomplete data on their marital status, which was only recorded for 68 married and 49 widowed women. This suggests that around 40% of the suspects were widows; widowhood – and the loss of a husband’s socio-economic and personal support – therefore increased vulnerability to accusation. Family and personal reputation mattered as well. Daughters of suspected witches risked being imagined as witches themselves; the first group of Essex women accused of witchcraft in 1645 included the two mother-daughter pairs of Anne and Rebecca West of Lawford and Anne Leech of Mistley and her married daughter Helen Clarke of Manningtree. A woman’s poor sexual reputation could also make her vulnerable; Ursula Kemp and Elizabeth Clarke, the first women accused of witchcraft in St Osyth in 1582 and Manningtree in 1645 respectively, had both had illegitimate children.

Accusations of witchcraft could also emerge from tensions in areas such as childbearing, childrearing, and domestic food production that were socially and culturally characterised as domestic and dominated by women. In this context, accusations were often made against women by other women, who used the accusation as a way of affirming their own status as ‘good’ housewives and ‘good’ mothers. This can be seen in the accusations made against Mary Johnson by Annabel Durrant and Elizabeth Otley in 1645 (see the Witchcraft Beliefs article for more detail). As well as acting as accusers and witnesses against other women, some women even became the watchers and body-searchers of suspects during the East Anglian trials of 1645, helping the witch-finders elicit confessions from female suspects.

Find the trail map at: https://essex-sunshine-coast.org.uk/